BUGGED OUT: Representations of Arthropods in Modern & Contemporary Art

May 6, 2019 - December 20, 2019

Humans have evolved relatively recently in a world long replete with Arthropods, which constitute the largest phylum of creatures on Earth both in terms of number of species and in total number of individuals. There are nearly a million species of Arthropods, with over 90% of them being insects. Sharing a world with this horde, humans have formed relationships with insects in many ways. Sometimes humans and insects influence each other minimally, other times we profoundly impact each other. Look for evidence of our relationship with insects and it will appear all around you, particularly in the works of artists.

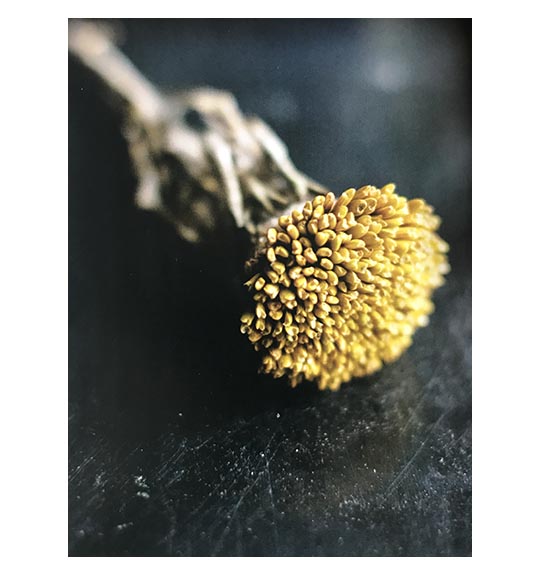

It is easy to see why artists might be inspired to depict an insect in their work. We marvel at the diversity of colors, forms, and behaviors of insects. As a species, we domesticate insects and exploit insect products (e.g., silk, beeswax, honey, cochineal, lacquer), include insects in our diet, language and recreational activities, base forensic investigations on carcass‐feeding insects, use insects as indicators of habitat quality, use them as model organisms for scientific research, and we pollute or radically alter habitats in an attempt to attract, repel, or extinguish species of insects. Some insects, in turn, pollinate our crops, use our homes for shelter, parasitize our bodies, spread pathogens and allergens, and feed on our resources and excrement and remains. Human‐insect interactions are so pervasive that insects often appear as central players, even as symbols, within politics, science and technology, religion, mythology and folklore, literature, poetry, music, the performing and visual arts, and recreation. Our relationship with insects has been recorded through the visual arts in ways and for a duration that is unmatched by any other source of information.

Artists have included insects in their works for a variety of reasons. Some sought and seek to adorn shelters or garments, or to record observations. Others have imbued insects with spiritual, or supernatural qualities. Supernatural associations with insects are often found in the form of totems and symbols. Insect symbols can hold great importance within societies, offering clear and powerful visual representations of ideas. Insects have symbolized many qualities, including change, industry, royalty, social harmony, might, pestilence, disease, death, etc. While certain insects inspire specific and somewhat universal symbolic associations (e.g., flies with pestilence, disease, or death), symbols are often contextually, culturally dependent. In modern cultures today, we can find insects symbolically on stamps and currency, in advertisements, even as visual representations of sports teams or military units.

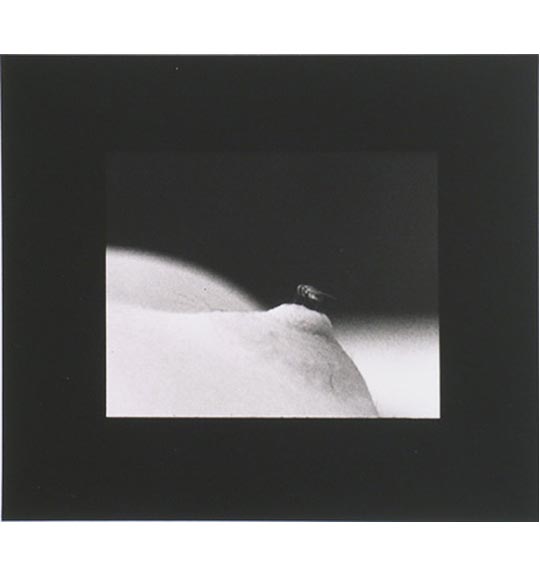

Insects make good symbols because they often induce emotional reactions in humans. Exploiting these reactions, artists have often included insects in their art to more clearly or powerfully express an idea. Politics, war, and environmental devastation are examples of themes that have inspired artists to generate insect art.

Recent examples of politically‐motivated insect art include anti‐Marxist ants, cockroach executions, a militaristic beetle, and ant flags. The anti‐Marxist ants are the product of Alberto Faietti, who has produced books of insects glued to pages. In one work, “the third letter of an ant community to karl marx,” Faietti commented on human socialism by forming elaborate text and equations, ending with the word “NO,” formed by the bodies of ants. The cockroach executions belong to Catherine Chalmers’ photographic and video series. Cockroaches appear to be electrocuted, hanged, or burned in staged executions that provoke questions about human execution practices. The militaristic beetle is the product of “Bansky,” an elusive artist based in the U.K. Bansky secretly hung a piece of anti‐war artwork in the American Museum of Natural History— a harlequin beetle equipped with sidewinder missiles and a satellite dish.

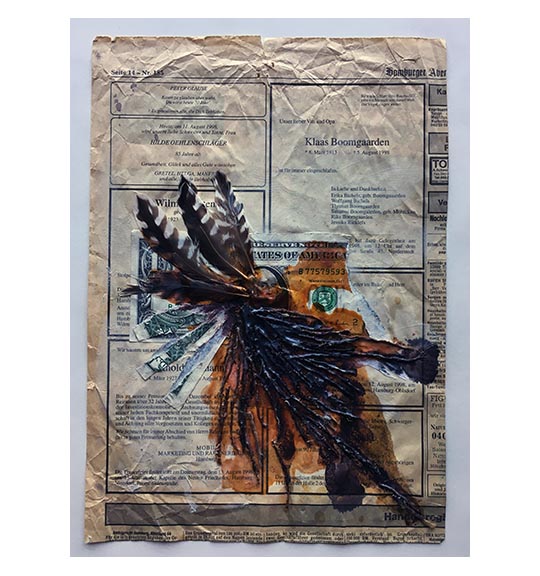

Yukinori Yanagi’s art, unlike the previous examples of politically‐motivated insect art, displays live insects. In most works, entire ant colonies are mounted in transparent displays of colorful sand arrangements, which form either political flags or paper currency. The ants displace the sand grains, breaking down the political boundaries initially set up by Yanagi.

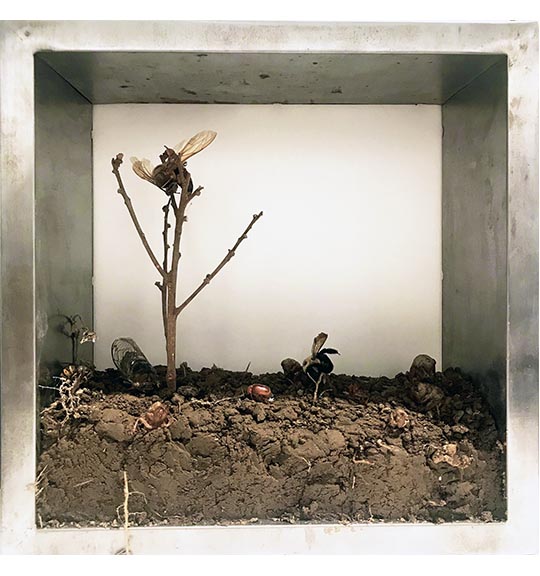

Environmentally‐motivated insect art is a category that has a more recent history than politically‐motivated insect art, due to awareness of large‐scale environmental disasters recently affecting our planet. The loss of biodiversity, natural resource depletion, and habitat destruction have all inspired artists to generate insect art. Artists create such examples of environmentally‐minded art in large part to generate attention needed to conserve nature and protect the diversity of life.

Insects serve as tools, including symbols, to evoke emotions. When emotional subjects, such as politics, war and environmental degradation are used as art themes, insects can help to elicit emotions that lend power to these themes.

HISTORY OF WESTERN INSECT ART

Although a great cultural heritage of insect art is found throughout the world, the most widely documented and accessible materials are associated with “Western” art. Prior to the 17th century, insects appeared in Western art as religiously‐charged symbols of the soul, ephemeral life, or Jesus Christ— appearing in religious texts and paintings of biblical scenes. Insects also appeared in portraits. Sometimes the realistic depiction of a fly on a portrait indicated that the subject of the portrait had died.

Due to the reformation of the Catholic church in the 16th century, iconoclasts temporarily instated a ban on religious imagery, resulting in a separation of Western art and religion. As a result, insects were used by artists for different purposes following the Reformation. Seventeenth century Belgium and the Netherlands spawned genres of art that were less religious, resulting in waves of landscapes and still lifes. Marcel Dicke (2000) spent three years documenting 1,942 examples of Western art featuring insects, after which he concluded that the 17th century constituted the richest period in Western history, both for total number of pieces featuring insects and diversity of insect orders represented. Most still lifes featured insects, and some, as Dicke calculated, included over 100 insects per painting. Examples of artists include Jan van Kessel the Elder (1626‐1679), Rachel Ruysch (1664‐1750), Jan van Huysum (1682‐ 1749) and, later, Paulus Theodorus van Brussel (1754‐1795). Several still life artists of the same period, most notably Maria Sibylla Merian, extended their talents to develop the science of entomology. Merian, and scientific illustrators since her time, have combined esthetics and realism to promote insect science through centuries of insect paintings and drawings.

Most 18th century Western insect art continued in the form of still lifes. Nineteenth century impressionism rarely focused on small arthropods, although James McNeill Whistler used a butterfly as his signature, and Vincent van Gogh prominently painted insects as subjects in the last years of his life. The turn of the 19th century through the 20th century, on the other hand, exploded with respect to the total number of insect art pieces. Art nouveau, surrealism, modern and contemporary art all prominently feature insects.

Art nouveau embraced natural motifs, and artists included insects in painting, sculpture, and utilitarian design such as glassware, furniture, and ceramics. Emile Gallé produced insectal furniture, and some of René Lalique’s most famous jewelry consisted of sculpted insects, and animal chimeras that display fabricated elements of insects.

“[Lalique] was well‐acquainted with the teeming multitude of insects of the meadow that leap from stalk to stalk—butterflies and wasps, grasshoppers, bumblebees, and beetles…” —Yvonne Brunhammer (1998)

The decorative (insect) arts achieved a zenith with Lalique and another French designer, E. A. Seguy. Seguy produced realistic and decorative assemblages of butterflies and other insects to promote the application of nature into the decorative arts.

Surrealism promoted liberation of the mind by attaining a state deemed truer than reality. Insects evidently feature prominently in this surreal state, because insects abound in the works of Salvador Dalí, James Ensor, René Magritte, and other surrealists.

MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY INSECT ART

Modern and contemporary artists from around the world continue to include insects in their work. The diversity of insect inclusions in modern‐day art is overwhelming, but one way to examine modern or contemporary insect art is to organize the art by degree of realism. A few examples follow.

Realistic insects: Realistic renderings of insects in art share a history harkening back at least to Albrecht Dürer’s Stag Beetle (1505). Realistic insects in contemporary art include paintings by Mark Fairnington, life‐size sculptures by Bill Logan and Tom Friedman, and magnified insect sculptures by Patrick Bremer and Lorenzo Possenti.

Realistic insects in unnatural settings: Surrealists’ works often fall in this category, and M. C. Escher’s illusory visions included ants and sequences of metamorphoses. David Prochaska depicted insects on a series of cans of insecticide, April Vollmer creates woodcuts of insect arrangements, and Karen Anne Klein produces still life thematic compositions that almost invariably feature realistic insects.

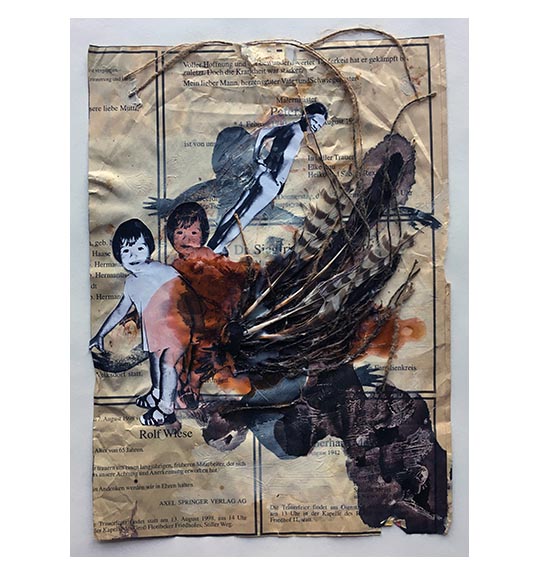

Loose renderings of insects: As with chalk drawings of early honey‐gatherers and Van Gogh’s impressionist pieces with insects, Joseph Beuys, Graham Sutherland, and Jean Émile Laboureur may have interpreted the lives of insects accurately, but depicted the actual insects with less scientific rigor.

Fantastical or abstract insects: Finally, the abstract representation of insects dates to stone drawings, insect totems and symbols, and is often extracted more from the mind of the artist than from the source of inspiration. Some modern examples of insect abstractions include works by André Masson, Joan Miro, Alexander Calder, Sue Johnson, and Francisco Toledo. Charles Burchfield suggested the presence of singing insects by painting waves representing sound generated by the insects.

Insect art can be made with any material, including the insects themselves. Beginning with bison bone and chalk on stone, insects have been depicted with materials ranging from metal cast from the lost (bees)wax process, to tattooed human flesh. Painted insects adorn Mimbres pottery from the North American Southwest, Greek ceramics, and Egyptian frescoes, along with most insect art throughout history. Sculpted insects can be carved, as with Edo Period insect wood carvings in Japan or Antonio Canova’s marble sculpture Cupid and Psyche. Sculpted insects can also be cast in a variety of materials, woven, or constructed from such random ingredients as Play Doh, “fuzz,” and plastic hair (Tom Friedman’s sculptures). Many insect artists use photography (e.g., works by Jacques Kerchache, Gregory Crewdson, and Catherine Chalmers), or film. Insect bodies can themselves be used as art media. Henry Dalton, a Victorian microscopist, arranged individual scales from butterfly wings into microscopic still lifes, and Jean Dubuffet assembled collages of entire butterfly wings. Some traditional people in the Amazon rainforest enhance their beauty by wearing jewelry composed of damselfly or beetle wings. Others display intact insect corpses in their works: Alberto Faietti adhered insects to pages of books (mentioned above). Kazuo Kadonaga reared 110,000 silkworm moths until the immatures attached their cocoons throughout wood crates, where they were ultimately killed and displayed. Jennifer Angus decorates entire rooms with geometric insect arrays and Jan Fabre coats structures with beetles or beetle wings, including ceiling and chandelier in the Royal Palace of Belgium. Other artists display live insects. Yukinori Yanagi produces live ant displays 7 (mentioned above) and Hubert Duprat manipulates immature caddisflies so that the cases they build are constructed of jewels supplied by the artist.

Insects have always been a part of the cultural history and creativity of our species. The spectrum of insect art recorded on the walls of ancient caves and on artefacts of past civilizations, and the exhibits and festivals dedicated to insect‐related art found in the streets and galleries of modern societies are a testament to this long and interesting relationship between insects and human artists. Insects provide inspiration, subject matter, and sometimes even the raw materials for the artisan. The ubiquitousness of insects and the boundless imagination and creativity of humans should ensure the continued relevance of insects in the artistic ventures of humans well into the future. Ultimately, all art can reveal aspects of our history, and insect art documents the history of our relationship with insects.

ARTISTS

Hans Bellmer, Robert Disraeli, Rick Hards, Heide Hatry, Georges Hugnet, Nils Karsten, Edmund Kesting, Myron Kozman, Yoko Ono, Gaston Paris, Franz Roh, Jindřich Štyrský, František Zelenka, Unica Zürn

RESOURCES

Exhibition checklist

SELECTED WORKS FROM THE EXHIBITION