PLEASE NOTE: FACE COVERINGS ARE REQUIRED IN THE GALLERY.

THE GALLERY IS OPEN BY APPOINTMENT ONLY. PLEASE EMAIL US AT INFO@UBUGALLERY.COM TO SCHEDULE A VISIT.

INTERWAR LATVIA: An Experiment in Graphic Design & Book Publishing, 1918–1939

On view through July 30, 2021

Latvia declared its independence in November 1918 and realized it in 1920, following centuries of oppression from Russia and Baltic Germany. The country was finally able to enjoy cultural, economic and, initially at least, political freedom. Owing to internal political stress, the latter was revoked by an authoritarian government in 1934, but economic prosperity still ensued. All of it came to an end with start of the Second World War in 1939 and the Soviet invasion of 1940, followed by Nazi occupation starting in 1942 and Soviet reoccupation in 1944.

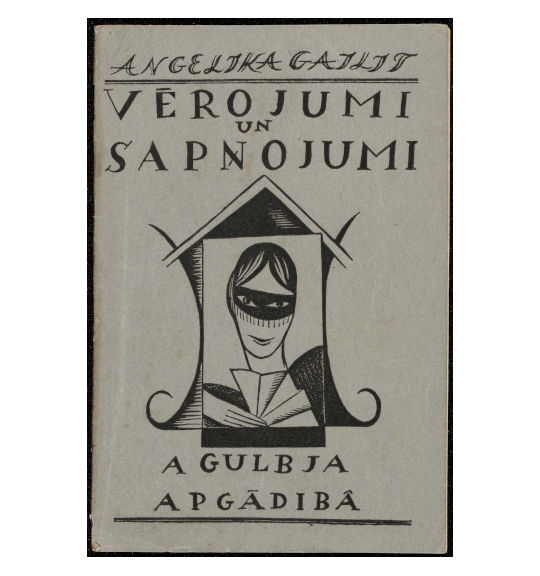

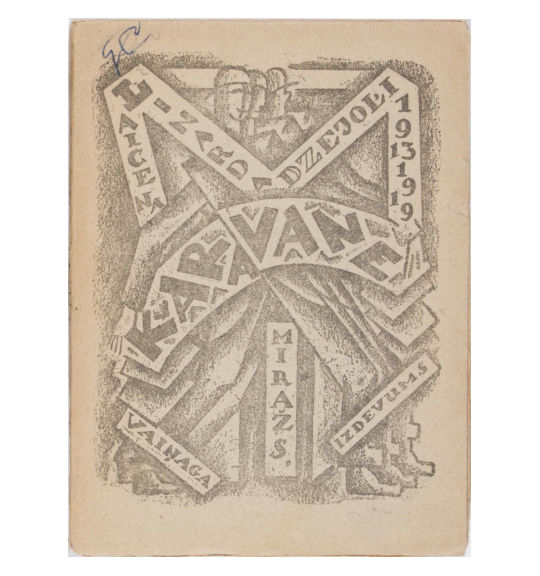

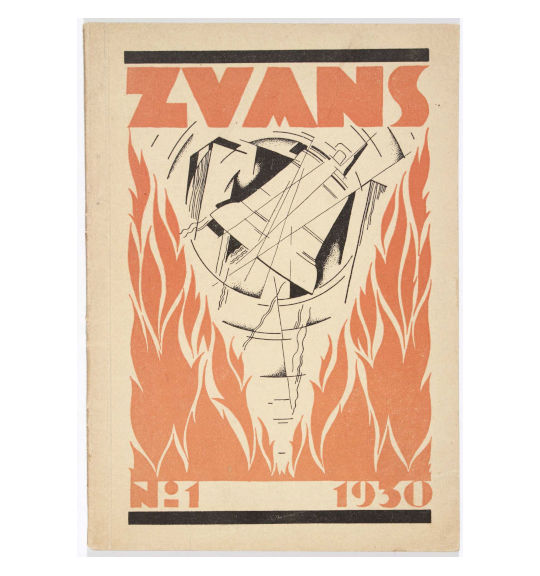

When Latvia achieved its first era of independence, it had a small and unclear visual culture and its artists began an earnest search for a national identity in visual expression. A lively, extensive book publishing industry had flourished under German rule and was fully operative as Latvian became the national language during the First World War. Numerous journals appeared, representing a full spectrum of political, economic, scientific and cultural trends.

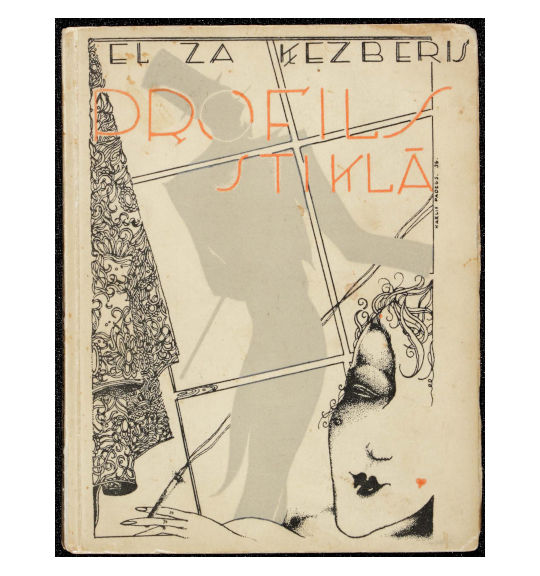

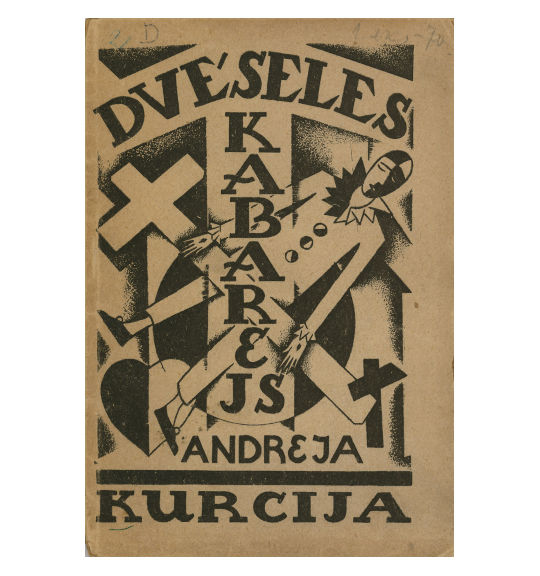

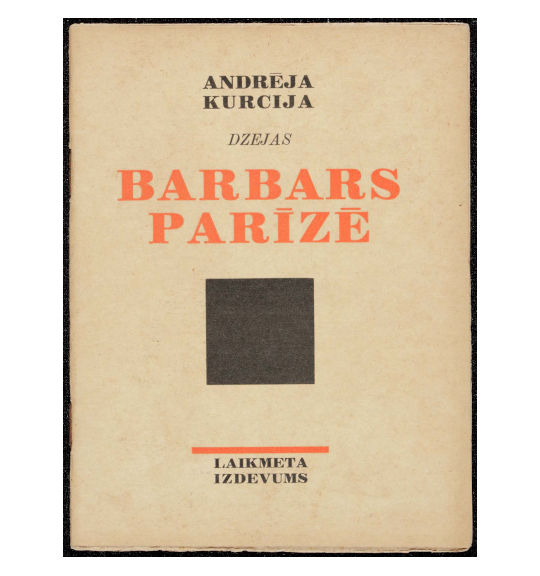

This period of experimentation in the arts and literature began in a search for new art forms, as well as in poetry, novels and music. The center of the most intense activity was the capital city of Riga, which also was its commercial and educational hub and the largest such in the Baltic States. Here an avant-garde group of artists emerged, with a parallel movement in “belles-lettres,” and both groups were closely interwoven. This exploratory period allowed artists to find a ready public in book and journal publishing, as well as establishing a framework for exhibitions.

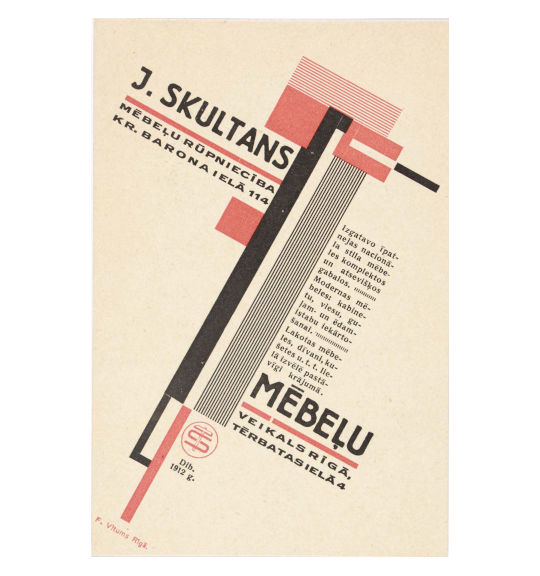

As Riga was also an international center, it produced a rich vein of books and periodicals in the Latvian, Russian, German and Yiddish languages. It already was a center of cosmopolitan visual outlook, embracing Jugendstil, Secessionist and Art Nouveau themes from abroad in architecture and ornamental design. Over the coming twenty years – particularly up until 1934 – publications and graphic design integrated Cubist, Expressionist, Constructivist and Bauhaus-related elements. In parallel, the folk-elements of nature spirits and mysticism were also incorporated, often side-by-side with Modernist trends, as an assurance that these new visual forms did not repudiate a living tradition by which the Latvians had survived – and had held dearly – under centuries of Russian and Teutonic dominance.

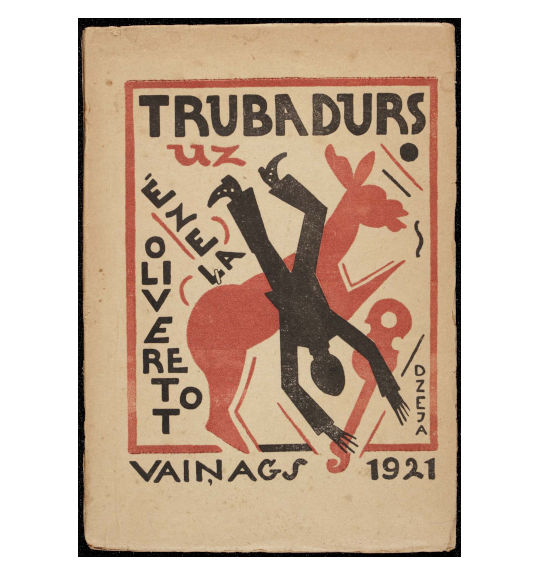

The Riga Artists’ Group was an association of painters and sculptors active from 1920–1940, with a Cubist period concentrated in 1923–1924. Oto Skulme, chairman of the group from 1923-1939, exhibited the first Cubist work in Riga, which he composed in 1920. Soon after he was joined in his interest in Cubism by other members of the Riga Artists’ Group – Romāns Suta (its first chairman), Jēkabs Kazaks, Konrāds Ubāns, Valdemārs Tone and others. These artists not only painted still lifes, but also depicted cafes, bars, circus scenes, vagrants and musicians. Through this a new range of motifs and images were introduced to Latvian art, specifically the atmosphere associated with an urban environment and lifestyle. The most active mouthpiece for the spirit of the new era in Latvia was Romāns Suta, who collaborated with Parisian Modernists. He published his findings in not only Latvian magazines, but also in the Parisian journal, L’Esprit nouveau, founded by architect Le Corbusier, poet Paul Dermée, and painter Amédée Ozenfant in 1920. Despite a changing membership, a relatively informal structure and internal disagreements about the specifics of a modernist agenda, the Riga Artists’ Group projected a unified identity in its 13 exhibitions. Ironically, after their Cubist show of 1923–1924 and their joint exhibitions with the “Group of Estonian Artists” and the Polish Constructivists of “Blok” (1924), Realism was reappearing as an artistic force and the members of the group were sharply berated by traditionalists who felt that their influences were outmoded. Shortly after, Suta and Aleksandra Beļcova, the more liberal members, left to undertake projects influenced by Purism and Constructivism, while most others turned towards Realism.

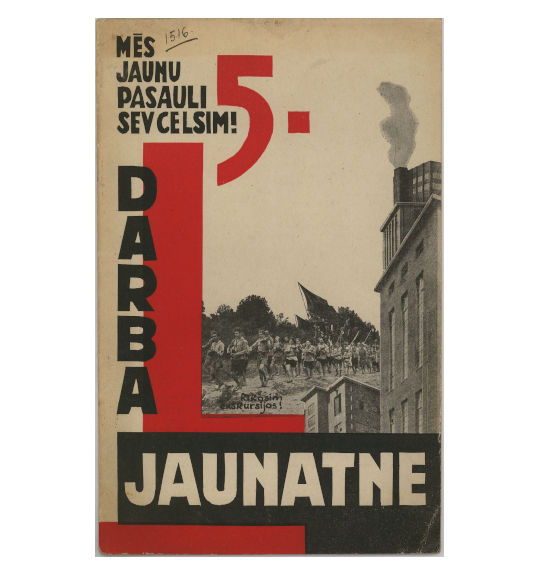

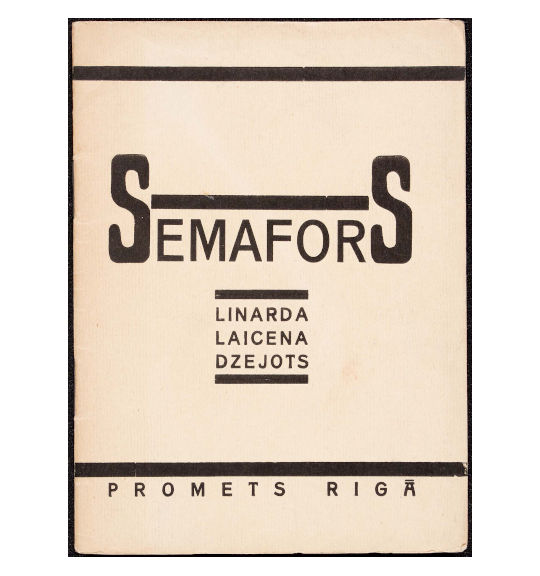

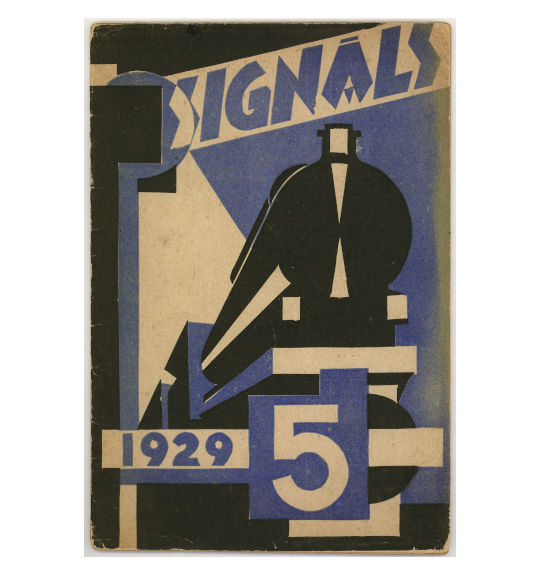

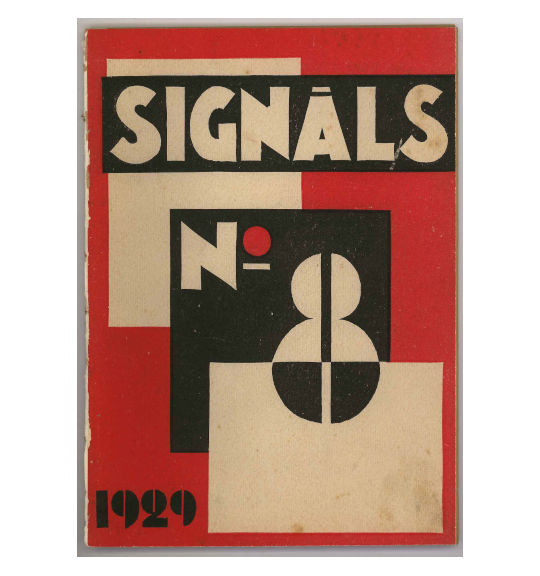

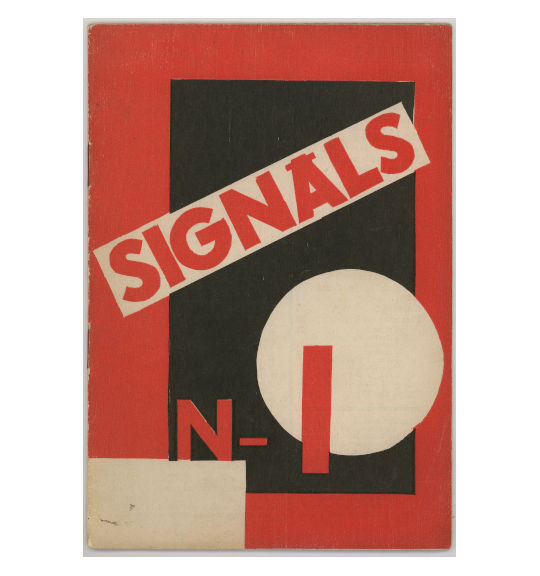

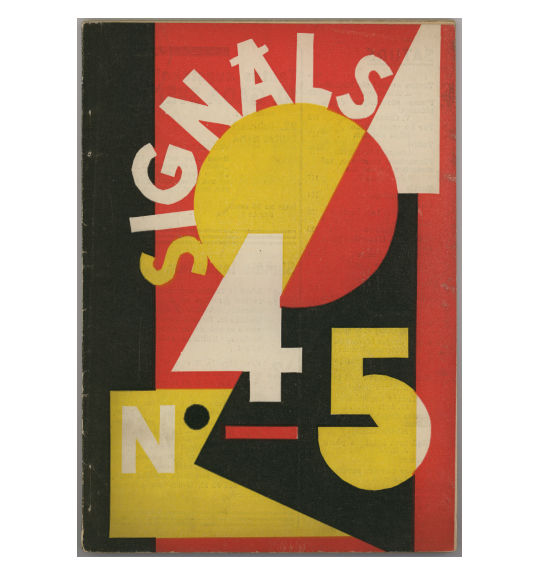

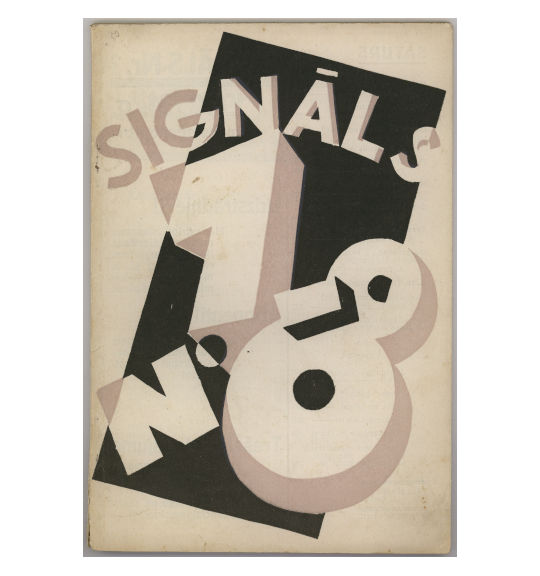

The Riga Artists’ Group also had a profound influence on book illustration, which can be seen in Ubu’s exhibition. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Constructivist elements and photomontage abound. Some of the most remarkable examples can be found on the covers of the journal Signāls (The Signal), which are strikingly original, even if most of the designers of these covers are anonymous. More fine examples of original Constructivist design are found in the journal Kreisa fronte (Red Front), also present here.

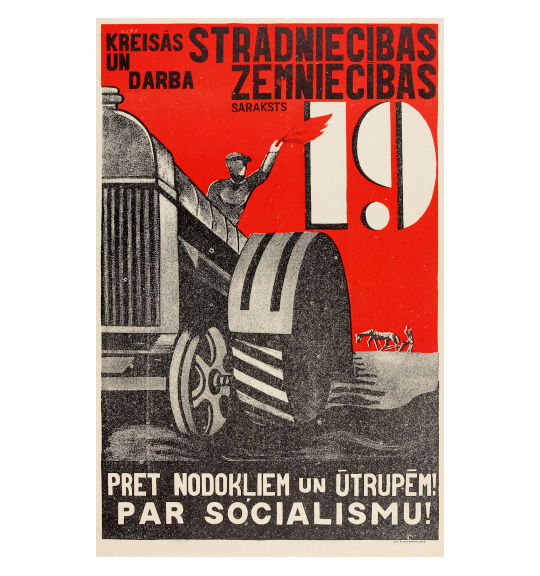

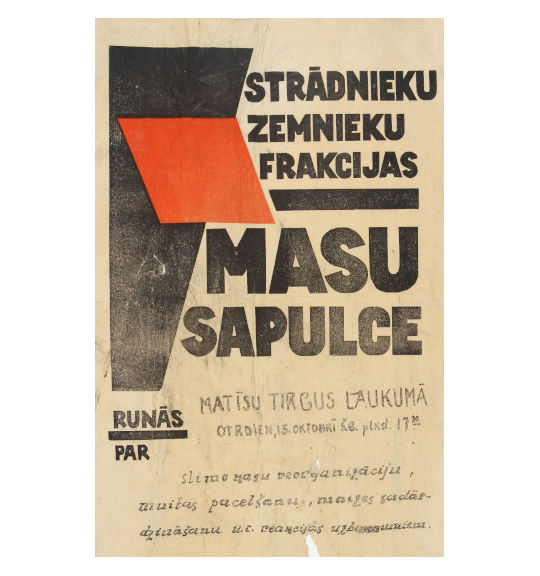

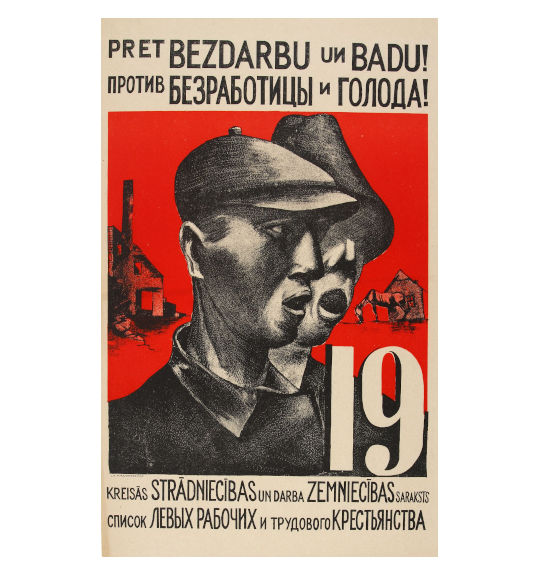

A few of the most important Latvian Modernists, including Suta, Niklāvs Strunke, Sigismunds Vidbergs, Jānis Liepiņš and Ludolfs Liberts, also designed posters. The posters in Ubu’s exhibition showcase just a few of the extensive collection of Latvian Modernist posters amassed by the gallery, which includes works by some of these influential artists. However, the majority of poster production in interwar Latvia was by anonymous graphic designers, often referencing Constructivist principles.

Almost all the avant-garde artists had leftist leanings. Two who achieved international renown, Gustavs Klucis and Aleksandrs Drēviņš, both left for the USSR to participate in the Soviet experiment. Throughout the 1920s and 30s, leftist publications featured work of the most creative minds in word, illustration, graphic design and protest. Ubu has a significant archive of these Latvian underground political publications or “Samizdat” (translating literally as “self-publishing”), including broadsheets, journals and announcements, many of them printed clandestinely and often using factory presses after-hours. This practice of secretive manual reproduction was widespread, due to the fact that most typewriters and printing devices were inventoried and controlled by the authorities, requiring permission to access. Possession of these grassroots publications, which were physically handed from reader to reader to evade official censorship, was fraught with danger and harsh punishments were meted out to those caught with censored materials. As such, surviving examples of these makeshift publications are exceedingly rare.

ARTISTS

RESOURCES

Exhibition checklist

Book descriptions

SELECTED WORKS FROM THE EXHIBITION